"I become very impatient with dreamers. I respect the doers more than the dreamers. So many people, it seems to me, talk about all the things they want to do. They only talk without accomplishing anything. The drifters are worse than the dreamers. Ones who really have no goals, no aspirations at all, just live from day to day..."

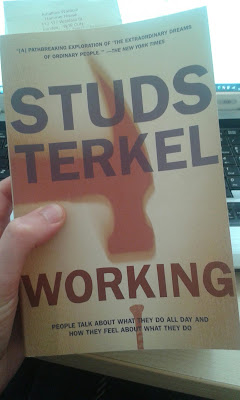

That's a quote from a private secretary called Anne Bogan who features in Working, Studs Terkel's groundbreaking sociological study of "people talking about what they do all day and how they feel about it", which I'm gradually working my way through in fits and starts.

I've had aspirations. I aspired to be a journalist, and now I am one. Now what?

In a recent post I quoted from Anna Karenina:

"He soon felt that the fulfillment of his desires had furnished him with only a grain of sand from that mountain of happiness which he had expected. This fulfillment showed him the constant mistake people make when they imagine that happiness lies in the fulfillment of desires."

Logically Tolstoy leaves us with three options: have no desires, have unfulfillable desires, or have many desires on the go, replacing the fulfilled ones with new unfulfilled ones at the same rate. Which of these did Tolstoy advocate?

He has a character who stands for himself explicitly say in Anna Karenina that "one must live for God and not for the satisfaction of one's needs", which is option one, but as an atheist that doesn't really work for me. Plus, we know from Anne, who stands for everyone in society, that this isn't accepted anyway.

And option three is no good: the difficulty of finding desires is the starting point for this post.

That leaves option two: have a small number of unfulfillable desires.

Tolstoy also makes clear in Anna Karenina that he thinks one should seek and find a family life. Human history also indicates this might be a good idea. And one can also live "not for the satisfaction of one's needs" if one instead lives for the satisfaction of other people's needs. We can desire good lives for our family, and this will be an unfulfilled (or at least ongoing) desire as long as you and they remain alive.

But people like people with goals, as we learnt from Anne. How would Anne react if she and I were on a first date and, in response to her asking me what my goal in life is, I were to say "To make you happy"? She would excuse herself and climb out the toilet window.

Besides, it's a circular proposition. If the only desire any of us can muster is the desire to fulfill others, there isn't anything for anyone to do.

Husband to wife: "What can I do for you today, my dear?"

Wife to husband: "Allow me to do something for you, my sweet!"

Husband to wife: "Erm..."

Wife to husband: "Allow me to do something for you, my sweet!"

Husband to wife: "Erm..."

Which is a roundabout way of arriving at: existentialism.

My next read is to be Nausea. But if my understanding is correct, that only offers an acute expression of the problem, and no answers.

Still, at least I want to read it, just about.